Thursday, September 22, 2005

Indonesia: Java

Indonesia, the world's largest archipelago spreading its 15'000 islands over 5200 km between the Asian mainland and Australia. So where to start? Given that we only could get a non-extensible 1 month visa, our travel had to be limited to a relatively small and not too remote part of the country. Java looked like a logical choice to begin.

Not the biggest island of the archipelago, but the most populous (holding over 50% of 225 million Indonesians), Java is the epicentre of the Indonesian state. Armed with an unreliable guide book (“Rough Guide to Indonesia”, latest edition, 2003) and an amusing compilation of past centuries traveller’s accounts (“Java, A Traveller’s Anthology”, James R.Rush), we set forth our own modest exploration, determined as ever to get through under our own steam and avoid ready-made tourist arrangements.

Java seems almost completely gardened by man’s hand. Still today, work in the fields is hardly mechanised. An endless carpet of plantations stretch over the plains and lower reaches of perfectly conical volcanic mountains. Rice, tobacco, tea, coffee, maize, areca, cabbage, tomatoes, potatoes, and much more cover the landscape. This sets a predominantly green tone, with a few dried patches of brown and yellow, and occasionally the liquid surface of newly planted padi field acting like mirrors.

Villages with neat red-tiled roofs pepper the fields. Nearing the city, their density increases until they form one big cluster, choked by traffic fumes. Until the construction boom of the 1990’s, even the capital Jakarta was a big amalgam of villages. Now, high rise offices and shopping malls mushroomed, linked by a tangle of flyovers and highways. Like elsewhere in S-E Asia (KL, Bangkok), strictly without prior urban planning!

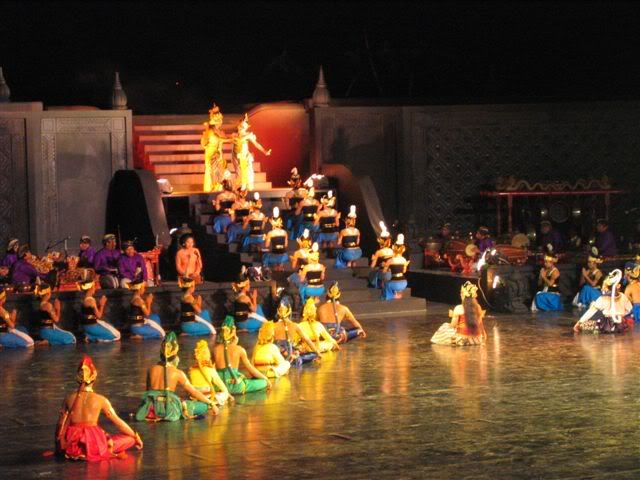

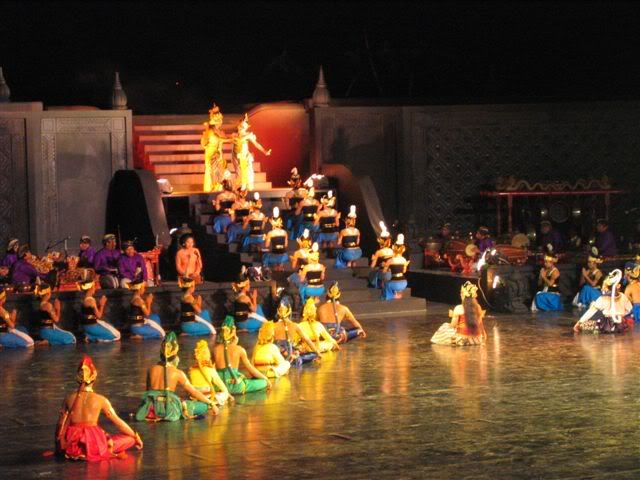

The sudden rash of modernisation didn’t affect the society in depth. The people of Java remain villagers and farmers, albeit ones with elaborate culture and traditions. Puppet shows, dances and theatre performances are still vivid. Most storylines improvised around the Indian Ramayana and Maharabata, with additions of comments and allusions to current events or situations. A gamelan orchestra provides musical accompaniement and interludes.

Indonesia might be the largest Islamic nation in the world, and the people of Java are surely devout Muslims, but, despite being converted since at least the 15th century, older beliefs survive. There are vigorous animist roots, the local pantheon of gods and spirits enhanced by Hinduist divinities. Shamanistic rituals, magic and some Buddhist and Hinduist rites obviously lurk under the surface of their Islam. Regularly, spectacular pilgrimages and processions take the way to old temples, or volcano craters to bring offerings. Dukuns (shamans) are called to help with a broad spectrum of problems, like to cure an illness, appease a superior at work, pass an exam, find love or a stolen motorcycle… This syncretism takes innumerable forms, and there are very strong regional variations.

In The Heart Of Javanese Culture

We started our journey with central Java. Around Yogyakarta and Solo. These two cities form the centre of Javanese culture. Together, they have 3 kratons (‘palaces’), holding the courts of the descendants of the Mataram rulers. The split of this once mighty empire occurred un the late 18th century, during the so-called 3rd Javan wars of succession. The Dutch, seeking to get a firmer grip on the island, successfully took advantage of internal dissent in the court to encourage division. Employees at the court in Yogyakarta, still wearing the traditional costume:

After this, unable to contest the Dutch, and reduced to a role of puppet rulers, the sultans patronised the arts and competed against each other through this medium. Nowadays, these sultans, especially Hamengkubuwono X of Yogyakarta, are still revered by the people of Java, and thus, have a strong influence on the politics of the country. They are mystic leaders, believed to have their power from Loro Kidul, the Goddess of the South Seas. Once a year, they are also entrusted to bring a buffalo’s head to the crater of Gunung Merapi, to appease the highly volatile volcano towering over the two cities.

The Javanese cultural life is very rich. We had the chance to see some shows. Most notably, the grandiose Ramayana ballets in Prambanan, quite touristy and easy to follow.

In Solo, we went to the theatre to see a piece based on episodes of the Maharabata, all in Javanese and difficult to understand, but the colours, sounds and dynamics alone were enough to make it worthwhile.

A becak driver waiting for customers. An unescapable reality in Yogyakarta and Solo. "Hello Mister, where you go?"

Famous Ruins

Central Java can boast two most impressive ruins, the remains of two rival kingdoms of the 8th-9th centuries. The Hinduist Sanjaya and the Buddhist Saliendra.

Borobudur is certainly the best known. This representation of the Buddhist cosmology is the biggest building of the southern hemisphere (at least in weight). It is a rather squat step pyramid, the big stupa crowning it hardly visible from the base. But its beauty lies in the details. The walls on the 4 bottom levels are richly decorated with bas-relief depicting scenes of everyday life, and stories of Buddha’s previous incarnations.

As one circles up, the themes get less earthly and more spiritual. The walls of the 4 higher levels are devoid of sculptures, just 72 hollow stupas containing each a statue of Buddha and a big empty stupa crowning the structure. The effect of reaching the upper levels after having gone around the lower levels is quite powerful. Like reaching the summit of a mountain, although Borobudur is not so high!

Near Borobudur, a small temple of the same period, named Candi Mendut contains one of the most beautiful statues of Buddha. “I know of no other single piece of sculpture which so successfully combines every canon into a whole of such complicated simplicity, so alive with dignity and holiness. Had I to chose an idol to pray to, this would be it.” wrote Geoffrey Gorer, a grumpy British esthete travelling Java in 1935. And there was the statue, sitting impassibly, totally unguarded.

The Hinduist temple complex of Prambanan, situated on a fertile plain in the suburbs of Yogyakarta, is the other UNESCO World Heritage site. It dates roughly from the same period as Borobudur.

Beside the main temple, many smaller ones lie scattered on the plain. They are less crowded and more atmospheric than the main temple. Sheep even graze undisturbed around the most remote… We reached them by bicycle: quite a nice ride on secondary roads, but not on the busy main fare, behind trucks and buses belching black smoke. Unfortunately, the latter were unavoidable.

We did a day trip to the countryside, 40 km away from Solo, to see Candi Sukuh, a classical Majapahit temple (14th century). The form was of a truncated pyramid, reminiscent of central America. It was also Hinduist, and dedicated to a cult of fertility. The location (on a hill) and the trip there were probably more memorable than the temple itself. We got there just seconds before the rain, and just about caught the last bus back to Solo. Everywhere on Java, public transport ceases with the arrival of the night at 6 pm!

Volcanoes

After visiting ruins and kratons, we ventured in the hinterland of central Java, to the small village of Selo. From there, we planned to climb Gunung Merapi, the ‘fire mountain’. Travelling to the northern slopes of the mountain by public transport is a small adventure in itself. The further we got, the rarer the public transport. Some places are only reachable on pick up truck, sharing the space with sacs of carrots and chicken.

The way up to the crater is a bit tricky, so we needed to hire a local guide. We left at 1 am, in order to be on top for the sunrise by 5.30 am. The first part of this steep ascension was through forests, but the last hour was up a hill of light volcanic rubble. From Merapi, the lights of Solo in the night:

Our efforts were rewarded by a breathtaking sunrise, shared with only one other tourist. Then we walked around the caldera. The mountain was hissing smelly sulphur that left bright yellow deposits at the vents; some stones were hot from the gas emanations. On the way down, we caught exceptional views of the lowlands and the neighbouring volcanic cones. Arriving at the villages at 9 am, life was in full swing, the markets busy, the workers in the fields.

Our next destination was the Dieng Plateau, which lies in a caldera. A kind of a miniature of the attractions of Java: bubbling mud craters, ruins of ancient temples, terrace cultivation and coloured sulphurous lake.

Getting there from Selo was a bit chaotic and exhausting, since the price of petrol just had doubled overnight, and many mini buses didn’t run. There were some demonstrations in bigger cities, but it was nowhere as bad as we feared. On that day, we experienced the best and the worse of Javanese travel: the few long-distance buses that ran where overloaded, many freelancers were trying to take advantage of the situation by proposing their transport at ludicrous prices, while others offered us a free ride and on one occasion, even cakes!

We stayed in Wonosobo, a town 1 hour by minibus from Dieng village. This was a good base to reach the place in the morning, before it got cloudy. The plateau was a sacred retreat, and the temples, built by the Sanjayas in the 7th century, though nowhere as grand as Prambanan, are the oldest on Java. Walking around was a pleasure, the people on the plateau were very friendly and happy to speak a few words with foreigners.

In Wonosobo, we met Ana, a young and motivated Indonesian woman teaching English. She was eager to show us around, and invited us to her school, where we spent an afternoon with teenage students. It was fun, and we were treated like VIP by the owners of the school, who offered us supper and rather unusual local delicacies to bring home (delicious dried bean and mushroom snacks). After this, she brought us to her home where we had the pleasure to meet her family (parents, uncles and cousins).

Bromo, in Eastern Java, was another long way from Dieng. To reach it, we had to break our journey in Surabaya, the second biggest town in Indonesia. A notoriously hot place (not only in temperature). But it wasn’t too bad.

Mount Bromo is in the Tengger massif. The Tengger are ethnically, culturally and linguistically different from the Javanese. Their largest festival, Kasada, where they throw offerings of flowers, vegetables and money into the Bromo crater had just taken place a couple of weeks before. Maybe a reason for the many decorations in the villages, that remained us of the animist signs we saw in some Tai-Lü temples in northern Laos.

We stayed 2 nights in Tosari, a village spread on a ridge, from where we hired two youngster and their motorbikes to bring us to view points and the crater the next day. It was the least touristy option we found. We left at 4 am to see the sunrise over the unique scenery of the smoking Bromo in the Sea of Sand, and the very active Semeru in the background spitting out debris every half hour or so.

This time, we had to share the view with busloads on tourists which do a halt there on the way from Yogyakarta to Bali. But it didn’t spoil our pleasure. Then we drove down across the Sea of Sand to the crater, through a landscape that could fit in the Gobi desert. Dusty horses can be hired for the few hundred meter from the parking area to the stairs leading up the crater. A ridiculous but picturesque side effect of mass tourism. The crater itself is a perfectly circular cauldron. An archetype!

Sunda And The Ramadan

We felt the first effects of the Ramadan in Tosari. It started on the 5th of October. During the fasting month, Muslims shouldn’t eat, drink or smoke during daytime unless they are too old, too young, sick or having menstruations. All the small food stalls and restaurants of Tosari were closed. So we had to rely on provisions bought in little shops. Out of respect, we ate them discreetely in the guesthouse room.

The nights were short. The chicken got awaken by the numerous musholas (small mosque) blaring out their calls for prayer at 4 am, sometimes broadcasting the whole half hour of the prayer. Normally, they are 5 prayers a day, but during Ramadan, a sixth is added at 23 pm. In Java, many start fasting as early as before the first prayer, when it is still pitch dark (sunrise usually occurs at 5.30 am). They get up around 3 pm for breakfast, then go praying and begin the day. Fast is officially broken around 6 pm, but many wait until the after the 7 pm evening prayer. As a result, people don’t sleep much at night, and they catch up during the day. Life slows down. We hardly came across somebody awake at a desk, and most shady places were occupied by sleepers.

Cultural events stop for Ramadan. Our intention was to go to the island of Madura after Bromo to see the bull races. But we were misinformed of the dates, and the tourism office of Surabaya assured us none were taking place during Ramadan. So we finally didn't go. The same occurred in Bandung, the capital of the province of West Java, and cultural centre of the Sundanese people, which have their own language and different traditions than the Javanese. No ram fights, jaipongan dances or wayang golek (a wooden puppet show). We had to be satisfied with a few Pop-Sunda and Keroncong music CDs bought at the market. Well, next time… Ramadan was also an interesting experience.

Hot Springs And More Volcanoes

One good effect of Ramadan is that it is the absolute low season for tourism. The hotel of West Java have unbeatable low rates, and reservations are not necessary on week-ends. During the rest of the year, the area is a hugely popular retreat for Jakartans, and gets overcrowded during days off.

We spent 3 days in Cipanas, near Garut. This low hill station is a couple of hours south of Bandung by bus. It lies at the foot of a volcano, and slightly sulphuric hot water is piped down to the whole village. We stayed in the best hotel in town, with swimming pool and hot spring water in the room. For under 20 Euro a night including a hearty breakfast buffet... A place where General Suharto, former president-dictator of Indonesia for 30 years, used to descend.

The area around Cipanas is pleasant. We did an excursion to one of the volcanoes, Papandayan, who was interesting enough with its many smoking vents. By now, we were used to the rotten egg smell.

Papandayan's last major eruption was in November 2002, and the dirt road leading to the remote valley behind the caldera was cut in many place. We followed this path for a couple of hours to the first fields where people were very welcoming and apparently not accustomed to strangers. The afternoon mist was already coming up, so we returned quite early. In Cisangkut, at the foot of the volcano, we walked around and found rice fields terracing the whole valley. The most beautiful we saw so far. Unfortunately, the weather was too overcast for good pictures.

Our last stop before Jakarta was the Gede Pangrango National Park, home to 3 varieties of the shy leaf monkeys and the rare Javan gibbon. We spotted two species of the first, and heard the whopping calls of the latter in the very early morning. The park is also a must for bird watchers (which we don’t have the knowledge to be). Else, there is a trail from the village of Cibodas, which is at the gates of the park, up to the twin cones of Gede and Pangrango, two volcanoes, the latter extinct.

Of course, we couldn’t refrain from climbing up to the Gede. As it already gets misty in the late morning, and thunderstorms and rain are very common in the late afternoon, it was important to leave early. We started at 1 am, and it took us 5.30 hours to get to the summit. This time, nobody else was there. We didn’t bother to take a guide as the trail was quite easy to follow and nowhere as dangerous as Merapi. On top, at 2900 meters, beside the usual crater, there were bushes of blueberries and Javan edelweiss, some in bloom. Quite an unusual sight under the tropics.

We also had a look at the 80 hectares botanical gardens of Cibodas, the lesser known extension of Bogor. They look tidy like a big French park. Unfortunately, the best parts (like the orchid green house), are closed to the public. Else, plenty of varieties of trees and a big rhododendron garden. As we are not botanists, it somehow failed to catch our attention.

Jakarta

We ended our trip in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, which has a reputation of being absolutely horrendous, congested and chaotic. But we found none of this. People were courteous and helpful, and traffic was not half as bad as Bangkok, or Kuala Lumpur. Probably because of Ramadan, or the sudden rise of fuel prices. On our last day, a new rule was introduced, imposing at least 3 people in every motorised vehicle due to fuel shortage…

Anyway, we enjoyed some time shopping (especially Claudia who got 4 pairs of elegant shoes!), and visiting parks and museums. We spent a rainy day at the Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, based on an idea of General Suharto's wife. Traditional houses from every province of Indonesia are more or less authentically represented around a lake. They contain exhibits, some much less worse than others (Papua was easily the best). There also were other museums (that we didn’t bother to see), a fresh water aquarium (good), an insectarium (also good), a sky train (the only one in the country, but we didn’t try it), and a map of Indonesia on the lake. The whole is not as tacky as it could be. We had the whole park for ourselves. On that day, they were maybe less than 20 visitors and most park employees were either sleeping or minding their own business.

The national museum was much better. It houses some of the best archeological finds of the archipelago. We followed a free tour by the German speaking association of Jakarta (founded by Germans, Austrian and Swiss expatriates). The guide had a good knowledge of Indonesia, and the 1.30 hours of the tour were over in an instant. We then mingled around on our own for a couple of hours, spending some time in the new wood carving hall that displayed an intriguing thematic collection of figurines from all over the country.

Finally, we went up the MONAS to catch a panoramic view of Jakarta. The 130 meters high monument representing a torch, probably supposed to cast light over the young republic after many dark years of colonial oppression. But it is better known as “Sukarno’s last erection”, after the first president of the Republic of Indonesia, a notorious womaniser who had a taste for monumental socialist architecture where size mattered more than style.

One more picture!

Finally, the mandatory picture of us. Can you guess where we are?

Not the biggest island of the archipelago, but the most populous (holding over 50% of 225 million Indonesians), Java is the epicentre of the Indonesian state. Armed with an unreliable guide book (“Rough Guide to Indonesia”, latest edition, 2003) and an amusing compilation of past centuries traveller’s accounts (“Java, A Traveller’s Anthology”, James R.Rush), we set forth our own modest exploration, determined as ever to get through under our own steam and avoid ready-made tourist arrangements.

Java seems almost completely gardened by man’s hand. Still today, work in the fields is hardly mechanised. An endless carpet of plantations stretch over the plains and lower reaches of perfectly conical volcanic mountains. Rice, tobacco, tea, coffee, maize, areca, cabbage, tomatoes, potatoes, and much more cover the landscape. This sets a predominantly green tone, with a few dried patches of brown and yellow, and occasionally the liquid surface of newly planted padi field acting like mirrors.

Villages with neat red-tiled roofs pepper the fields. Nearing the city, their density increases until they form one big cluster, choked by traffic fumes. Until the construction boom of the 1990’s, even the capital Jakarta was a big amalgam of villages. Now, high rise offices and shopping malls mushroomed, linked by a tangle of flyovers and highways. Like elsewhere in S-E Asia (KL, Bangkok), strictly without prior urban planning!

The sudden rash of modernisation didn’t affect the society in depth. The people of Java remain villagers and farmers, albeit ones with elaborate culture and traditions. Puppet shows, dances and theatre performances are still vivid. Most storylines improvised around the Indian Ramayana and Maharabata, with additions of comments and allusions to current events or situations. A gamelan orchestra provides musical accompaniement and interludes.

Indonesia might be the largest Islamic nation in the world, and the people of Java are surely devout Muslims, but, despite being converted since at least the 15th century, older beliefs survive. There are vigorous animist roots, the local pantheon of gods and spirits enhanced by Hinduist divinities. Shamanistic rituals, magic and some Buddhist and Hinduist rites obviously lurk under the surface of their Islam. Regularly, spectacular pilgrimages and processions take the way to old temples, or volcano craters to bring offerings. Dukuns (shamans) are called to help with a broad spectrum of problems, like to cure an illness, appease a superior at work, pass an exam, find love or a stolen motorcycle… This syncretism takes innumerable forms, and there are very strong regional variations.

In The Heart Of Javanese Culture

We started our journey with central Java. Around Yogyakarta and Solo. These two cities form the centre of Javanese culture. Together, they have 3 kratons (‘palaces’), holding the courts of the descendants of the Mataram rulers. The split of this once mighty empire occurred un the late 18th century, during the so-called 3rd Javan wars of succession. The Dutch, seeking to get a firmer grip on the island, successfully took advantage of internal dissent in the court to encourage division. Employees at the court in Yogyakarta, still wearing the traditional costume:

After this, unable to contest the Dutch, and reduced to a role of puppet rulers, the sultans patronised the arts and competed against each other through this medium. Nowadays, these sultans, especially Hamengkubuwono X of Yogyakarta, are still revered by the people of Java, and thus, have a strong influence on the politics of the country. They are mystic leaders, believed to have their power from Loro Kidul, the Goddess of the South Seas. Once a year, they are also entrusted to bring a buffalo’s head to the crater of Gunung Merapi, to appease the highly volatile volcano towering over the two cities.

The Javanese cultural life is very rich. We had the chance to see some shows. Most notably, the grandiose Ramayana ballets in Prambanan, quite touristy and easy to follow.

In Solo, we went to the theatre to see a piece based on episodes of the Maharabata, all in Javanese and difficult to understand, but the colours, sounds and dynamics alone were enough to make it worthwhile.

A becak driver waiting for customers. An unescapable reality in Yogyakarta and Solo. "Hello Mister, where you go?"

Famous Ruins

Central Java can boast two most impressive ruins, the remains of two rival kingdoms of the 8th-9th centuries. The Hinduist Sanjaya and the Buddhist Saliendra.

Borobudur is certainly the best known. This representation of the Buddhist cosmology is the biggest building of the southern hemisphere (at least in weight). It is a rather squat step pyramid, the big stupa crowning it hardly visible from the base. But its beauty lies in the details. The walls on the 4 bottom levels are richly decorated with bas-relief depicting scenes of everyday life, and stories of Buddha’s previous incarnations.

As one circles up, the themes get less earthly and more spiritual. The walls of the 4 higher levels are devoid of sculptures, just 72 hollow stupas containing each a statue of Buddha and a big empty stupa crowning the structure. The effect of reaching the upper levels after having gone around the lower levels is quite powerful. Like reaching the summit of a mountain, although Borobudur is not so high!

Near Borobudur, a small temple of the same period, named Candi Mendut contains one of the most beautiful statues of Buddha. “I know of no other single piece of sculpture which so successfully combines every canon into a whole of such complicated simplicity, so alive with dignity and holiness. Had I to chose an idol to pray to, this would be it.” wrote Geoffrey Gorer, a grumpy British esthete travelling Java in 1935. And there was the statue, sitting impassibly, totally unguarded.

The Hinduist temple complex of Prambanan, situated on a fertile plain in the suburbs of Yogyakarta, is the other UNESCO World Heritage site. It dates roughly from the same period as Borobudur.

Beside the main temple, many smaller ones lie scattered on the plain. They are less crowded and more atmospheric than the main temple. Sheep even graze undisturbed around the most remote… We reached them by bicycle: quite a nice ride on secondary roads, but not on the busy main fare, behind trucks and buses belching black smoke. Unfortunately, the latter were unavoidable.

We did a day trip to the countryside, 40 km away from Solo, to see Candi Sukuh, a classical Majapahit temple (14th century). The form was of a truncated pyramid, reminiscent of central America. It was also Hinduist, and dedicated to a cult of fertility. The location (on a hill) and the trip there were probably more memorable than the temple itself. We got there just seconds before the rain, and just about caught the last bus back to Solo. Everywhere on Java, public transport ceases with the arrival of the night at 6 pm!

Volcanoes

After visiting ruins and kratons, we ventured in the hinterland of central Java, to the small village of Selo. From there, we planned to climb Gunung Merapi, the ‘fire mountain’. Travelling to the northern slopes of the mountain by public transport is a small adventure in itself. The further we got, the rarer the public transport. Some places are only reachable on pick up truck, sharing the space with sacs of carrots and chicken.

The way up to the crater is a bit tricky, so we needed to hire a local guide. We left at 1 am, in order to be on top for the sunrise by 5.30 am. The first part of this steep ascension was through forests, but the last hour was up a hill of light volcanic rubble. From Merapi, the lights of Solo in the night:

Our efforts were rewarded by a breathtaking sunrise, shared with only one other tourist. Then we walked around the caldera. The mountain was hissing smelly sulphur that left bright yellow deposits at the vents; some stones were hot from the gas emanations. On the way down, we caught exceptional views of the lowlands and the neighbouring volcanic cones. Arriving at the villages at 9 am, life was in full swing, the markets busy, the workers in the fields.

Our next destination was the Dieng Plateau, which lies in a caldera. A kind of a miniature of the attractions of Java: bubbling mud craters, ruins of ancient temples, terrace cultivation and coloured sulphurous lake.

Getting there from Selo was a bit chaotic and exhausting, since the price of petrol just had doubled overnight, and many mini buses didn’t run. There were some demonstrations in bigger cities, but it was nowhere as bad as we feared. On that day, we experienced the best and the worse of Javanese travel: the few long-distance buses that ran where overloaded, many freelancers were trying to take advantage of the situation by proposing their transport at ludicrous prices, while others offered us a free ride and on one occasion, even cakes!

We stayed in Wonosobo, a town 1 hour by minibus from Dieng village. This was a good base to reach the place in the morning, before it got cloudy. The plateau was a sacred retreat, and the temples, built by the Sanjayas in the 7th century, though nowhere as grand as Prambanan, are the oldest on Java. Walking around was a pleasure, the people on the plateau were very friendly and happy to speak a few words with foreigners.

In Wonosobo, we met Ana, a young and motivated Indonesian woman teaching English. She was eager to show us around, and invited us to her school, where we spent an afternoon with teenage students. It was fun, and we were treated like VIP by the owners of the school, who offered us supper and rather unusual local delicacies to bring home (delicious dried bean and mushroom snacks). After this, she brought us to her home where we had the pleasure to meet her family (parents, uncles and cousins).

Bromo, in Eastern Java, was another long way from Dieng. To reach it, we had to break our journey in Surabaya, the second biggest town in Indonesia. A notoriously hot place (not only in temperature). But it wasn’t too bad.

Mount Bromo is in the Tengger massif. The Tengger are ethnically, culturally and linguistically different from the Javanese. Their largest festival, Kasada, where they throw offerings of flowers, vegetables and money into the Bromo crater had just taken place a couple of weeks before. Maybe a reason for the many decorations in the villages, that remained us of the animist signs we saw in some Tai-Lü temples in northern Laos.

We stayed 2 nights in Tosari, a village spread on a ridge, from where we hired two youngster and their motorbikes to bring us to view points and the crater the next day. It was the least touristy option we found. We left at 4 am to see the sunrise over the unique scenery of the smoking Bromo in the Sea of Sand, and the very active Semeru in the background spitting out debris every half hour or so.

This time, we had to share the view with busloads on tourists which do a halt there on the way from Yogyakarta to Bali. But it didn’t spoil our pleasure. Then we drove down across the Sea of Sand to the crater, through a landscape that could fit in the Gobi desert. Dusty horses can be hired for the few hundred meter from the parking area to the stairs leading up the crater. A ridiculous but picturesque side effect of mass tourism. The crater itself is a perfectly circular cauldron. An archetype!

Sunda And The Ramadan

We felt the first effects of the Ramadan in Tosari. It started on the 5th of October. During the fasting month, Muslims shouldn’t eat, drink or smoke during daytime unless they are too old, too young, sick or having menstruations. All the small food stalls and restaurants of Tosari were closed. So we had to rely on provisions bought in little shops. Out of respect, we ate them discreetely in the guesthouse room.

The nights were short. The chicken got awaken by the numerous musholas (small mosque) blaring out their calls for prayer at 4 am, sometimes broadcasting the whole half hour of the prayer. Normally, they are 5 prayers a day, but during Ramadan, a sixth is added at 23 pm. In Java, many start fasting as early as before the first prayer, when it is still pitch dark (sunrise usually occurs at 5.30 am). They get up around 3 pm for breakfast, then go praying and begin the day. Fast is officially broken around 6 pm, but many wait until the after the 7 pm evening prayer. As a result, people don’t sleep much at night, and they catch up during the day. Life slows down. We hardly came across somebody awake at a desk, and most shady places were occupied by sleepers.

Cultural events stop for Ramadan. Our intention was to go to the island of Madura after Bromo to see the bull races. But we were misinformed of the dates, and the tourism office of Surabaya assured us none were taking place during Ramadan. So we finally didn't go. The same occurred in Bandung, the capital of the province of West Java, and cultural centre of the Sundanese people, which have their own language and different traditions than the Javanese. No ram fights, jaipongan dances or wayang golek (a wooden puppet show). We had to be satisfied with a few Pop-Sunda and Keroncong music CDs bought at the market. Well, next time… Ramadan was also an interesting experience.

Hot Springs And More Volcanoes

One good effect of Ramadan is that it is the absolute low season for tourism. The hotel of West Java have unbeatable low rates, and reservations are not necessary on week-ends. During the rest of the year, the area is a hugely popular retreat for Jakartans, and gets overcrowded during days off.

We spent 3 days in Cipanas, near Garut. This low hill station is a couple of hours south of Bandung by bus. It lies at the foot of a volcano, and slightly sulphuric hot water is piped down to the whole village. We stayed in the best hotel in town, with swimming pool and hot spring water in the room. For under 20 Euro a night including a hearty breakfast buffet... A place where General Suharto, former president-dictator of Indonesia for 30 years, used to descend.

The area around Cipanas is pleasant. We did an excursion to one of the volcanoes, Papandayan, who was interesting enough with its many smoking vents. By now, we were used to the rotten egg smell.

Papandayan's last major eruption was in November 2002, and the dirt road leading to the remote valley behind the caldera was cut in many place. We followed this path for a couple of hours to the first fields where people were very welcoming and apparently not accustomed to strangers. The afternoon mist was already coming up, so we returned quite early. In Cisangkut, at the foot of the volcano, we walked around and found rice fields terracing the whole valley. The most beautiful we saw so far. Unfortunately, the weather was too overcast for good pictures.

Our last stop before Jakarta was the Gede Pangrango National Park, home to 3 varieties of the shy leaf monkeys and the rare Javan gibbon. We spotted two species of the first, and heard the whopping calls of the latter in the very early morning. The park is also a must for bird watchers (which we don’t have the knowledge to be). Else, there is a trail from the village of Cibodas, which is at the gates of the park, up to the twin cones of Gede and Pangrango, two volcanoes, the latter extinct.

Of course, we couldn’t refrain from climbing up to the Gede. As it already gets misty in the late morning, and thunderstorms and rain are very common in the late afternoon, it was important to leave early. We started at 1 am, and it took us 5.30 hours to get to the summit. This time, nobody else was there. We didn’t bother to take a guide as the trail was quite easy to follow and nowhere as dangerous as Merapi. On top, at 2900 meters, beside the usual crater, there were bushes of blueberries and Javan edelweiss, some in bloom. Quite an unusual sight under the tropics.

We also had a look at the 80 hectares botanical gardens of Cibodas, the lesser known extension of Bogor. They look tidy like a big French park. Unfortunately, the best parts (like the orchid green house), are closed to the public. Else, plenty of varieties of trees and a big rhododendron garden. As we are not botanists, it somehow failed to catch our attention.

Jakarta

We ended our trip in Jakarta, the capital of Indonesia, which has a reputation of being absolutely horrendous, congested and chaotic. But we found none of this. People were courteous and helpful, and traffic was not half as bad as Bangkok, or Kuala Lumpur. Probably because of Ramadan, or the sudden rise of fuel prices. On our last day, a new rule was introduced, imposing at least 3 people in every motorised vehicle due to fuel shortage…

Anyway, we enjoyed some time shopping (especially Claudia who got 4 pairs of elegant shoes!), and visiting parks and museums. We spent a rainy day at the Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, based on an idea of General Suharto's wife. Traditional houses from every province of Indonesia are more or less authentically represented around a lake. They contain exhibits, some much less worse than others (Papua was easily the best). There also were other museums (that we didn’t bother to see), a fresh water aquarium (good), an insectarium (also good), a sky train (the only one in the country, but we didn’t try it), and a map of Indonesia on the lake. The whole is not as tacky as it could be. We had the whole park for ourselves. On that day, they were maybe less than 20 visitors and most park employees were either sleeping or minding their own business.

The national museum was much better. It houses some of the best archeological finds of the archipelago. We followed a free tour by the German speaking association of Jakarta (founded by Germans, Austrian and Swiss expatriates). The guide had a good knowledge of Indonesia, and the 1.30 hours of the tour were over in an instant. We then mingled around on our own for a couple of hours, spending some time in the new wood carving hall that displayed an intriguing thematic collection of figurines from all over the country.

Finally, we went up the MONAS to catch a panoramic view of Jakarta. The 130 meters high monument representing a torch, probably supposed to cast light over the young republic after many dark years of colonial oppression. But it is better known as “Sukarno’s last erection”, after the first president of the Republic of Indonesia, a notorious womaniser who had a taste for monumental socialist architecture where size mattered more than style.

One more picture!

Finally, the mandatory picture of us. Can you guess where we are?