Sunday, October 23, 2005

Indonesia: Sulawesi

After a short interlude in KL and Singapore for visa reasons, we flew to Sulawesi for one last month of travelling, still armed, like for Java, with our unreliable "Rough Guide to Indonesia" and an occasionally entertaining anthology of travel writings for Eastern Indonesia ("To The Spice Islands and Beyond", compiled and introduced by George Miller, Oxford in Asia Paperbacks).

Sulawesi is a large island that extends its peninsulas like tentacles East of Borneo. Its convolutions led the Portuguese to believe, on first coming here, that they found a group of islands, which they named "the" Celebes, not realising the peninsulas were connected.

Sulawesi's geography is very rugged. Separated by steep mountains ranges, the people of the different peninsulas, developed distinct cultures. On this trip, we focused on the Southwestern finger, which contains most of the lowlands and population of Sulawesi, and the Northern tip, which has some exceptional dive sites and good national parks. We took a flight (1h30) between those regions, avoiding the troubled Poso region in central Sulawesi and a harassing 5 days bus trip.

We hit Sulawesi end of October, at the beginning of the rainy season. In the morning, it was usually sunny. Being near the equator, the light turned very bright after 10am, and it felt hot and heavy. In the early afternoon, clouds would appear and we had rain almost every evening. Usually short showers, seldom downpours that continued during the night. The quality of the photos suffered a bit from the poor light conditions. This was aggravated by the fact that our digital camera, now in its 16th month of travelling, showed signs of exhaustion and had some problems in focusing and evaluating the brightness. A bit like us!

On Bugis And Makassarese

We started our ramblings in Makassar, the biggest city of Sulawesi and a busy commercial hub.

The population of the Southwestern peninsula is in majority Bugis and Makassarese. Theodora Benson, who travelled to Sulawesi in the 1930s wrote: "The Bugis and the Makassarese of the South are always spoken as two distinct races, but in descriptions of them no distinction between them appears at all except that their languages (of the Malayo-Javanese group) are very slightly different, at that the Bugis are a bit more seagoing and the Makassarese more agricultural. They are Mohammedans, with a touch of Hinduism and paganism, and women have a high and favourable position. They build magnificent prahus and navigate fearlessly. [] On many distant islands, a Bugis colony is found. They are energetic and spirited people, devoted to fun and gambling and good trade".

The distinction between Makassarese and Bugis probably came from the fact they were never really unified, and had historically had many competing kingdoms. The Dutch made use of those divisions to eventually completely subjugate them in 1909. We should also add that the Europeans, whose ships they often hijacked, feared them a lot. This earned the Bugis a lasting reputation as bloodthirsty pirates!

Makassar still has some remnants of the past, like Fort Rotterdam, a fortress whose origin is contested. The name would suggest the Dutch built it, but many think a Makassarese fort stood there before. There is also the more interesting and lively Paotere port. Paotere is the bustling base of what is probably the last non-motorised commercial fleet in the world. The majestic prahus, powered solely by the wind blowing in their sails, sternly await the cargo they'll be delivering all across the Indonesian archipelago.

According to our guidebook, a visit to Makassar is not complete without a meal at the cheap nocturnal seafood stalls along the sea promenade, which are so highly recommended as to be one of the highlights of Sulawesi! In fact, small affairs with dubious hygiene selling low-grade quality that failed to impress us. Else, we experienced the usual heat, stench and chaotic traffic of thousands of minibuses and tri-cycles honking and ringing every time they past us. But most of the people were very nice. For example, the tourist information our guidebook indicated, in fact a police station in the dusty and pointless museum, had only their total lack of knowledge on the city to match their eagerness to help and curiosity! Leaving their office, we were not quite sure they had seen any tourists before us...

Leaving Makassar was like breathing again. We enjoyed rather agreeable bus rides through coastal lowlands covered by wet rice fields, which offer a breathtaking tableau from the airplane, passing peaceful small towns and villages. We didn't explore much of the Bugis countryside though.

On our way to the Toraja highlands, we stayed one night in Polewali on the west coast of the peninsula, in an extremely friendly home-stay who hadn't seen many foreign guests before. The next morning was a Sunday. We took a walk to the weekly market, passing a few interesting ships on the beach. The weather was clouded and rainy, so we decided not to go to the Mandar heartland a couple of hours further along the coast. We proceeded instead directly to the Western Torajan highlands.

On our way back from the highlands, we did a stop in Sengkang, on the East coast of the peninsula. . Sengkang is on the shores of a lake system, on which fishermen communities live in floating shacks. A silk industry has been implemented in this region since the beginning of the 1990s, with the help of Thailand. We hoped to find some good material for Claudia's mother, but the quality, patterns and colours on offer in town were disappointing.

Life And Death In Torajaland

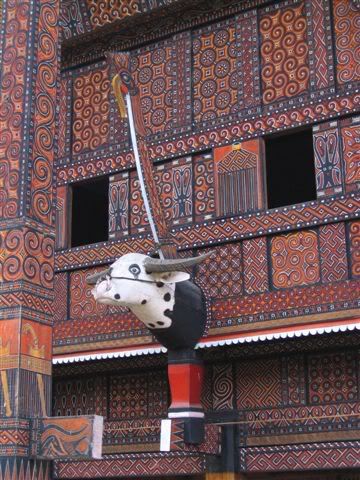

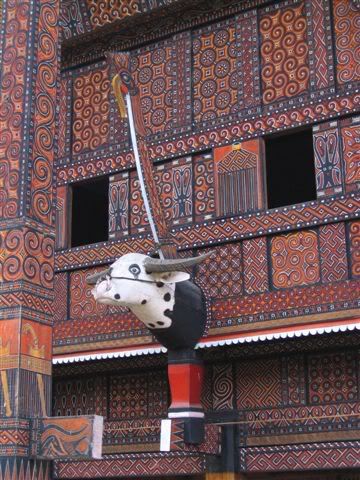

What we call Torajaland spans over two districts: Western Toraja (better known as Mamasa by the locals), and Tanah Toraja (also very “Indonesianly” abbreviated Tator). They are slight differences between the people of the two areas, most notably in the architecture (the Tator roofs are more up curved), the dialects and the art (they use different symbols, but the base colours stay the same). Typical carvings on the front of a house:

The word Toraja comes from the Bugis, and means "mountain people". There was never a unified Toraja kingdom. The villages had all their own nobility and used to fight quite often. Human sacrifices at funeral ceremonies and headhunting were also practised.

We started our Toraja circuit in Mamasa, which is the capital of the western district. The 90km trip from Polewali took 5 hours up a winding road in a new Kijang 4-wheel-drive. Mamasa itself had a few nice traditional houses and lots of half empty government buildings.

The bucolic walks to the surrounding villages were more attractive. There, we were once again the centre of attention; children springing out of nowhere like jack-in-the-box quipping "hello mister!", and adults continuously inquiring about where we wanted to go ("mau ke mana?" a common Indonesian greeting).

We spent a few days in Mamasa to gather some information on the region, the guidebooks just sparing at most a few lines on the subject. We met some helpful locals at the guesthouse, and we managed to gather intelligence from them around a few rounds of "balok" (a homemade mild palm wine). They told us about an important funeral in Bittuang, which happened to be on our itinerary. They also presented us to the Governor of the Mamasa province, who, after self-importantly telling us about tourism promotion in his district, wrote us a letter of recommendation.

So, we started our trek across Torajaland with this official blessing. The walk was going to take 3 days. Shortly after we started, we met Deny, a local nobleman living in an impressive traditional house. He invited us in for tea. He had studied anthropology, his English was very good and he was a trove of information on Western Toraja. He also had planned to go to the big funeral in Bittuang. When he finally proposed to guide us for a small fee, we accepted.

The path was not hard to find, we just had to follow the incredibly bumpy "Trans-Mamasa highway", not really suited for motorised vehicles. Deny showed us a few shortcuts and cooler alternatives, but most of the time we had to use the unshaded, stony road at the mercy of the sun.

En route, we learned about the strict Toraja class system (4 levels, from nobility down to serfdom), some symbols on houses and rice barns, the importance of cardinal directions in their cosmology, the differences between Mamasa and Tator, funeral ceremonies, reburial rituals, weddings, etc. We often stopped to chat under the ornate rice barns with Deny’s friends and relatives, and thus got acquainted with Torajan everyday life.

We saw that despite being officially in majority Christians, the Torajans still follow many rites and traditions of their ancient animist faith. Indonesian syncretism again! In Timbaan, the small hamlet where we did our first stop, the old bomoh (i.e. shaman) came with his flute to play traditional music.

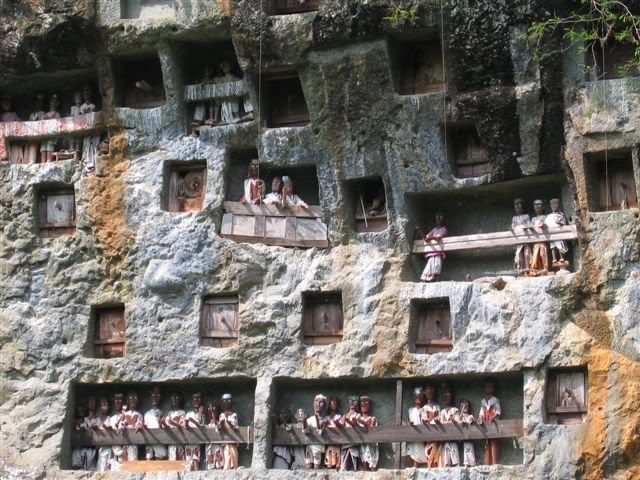

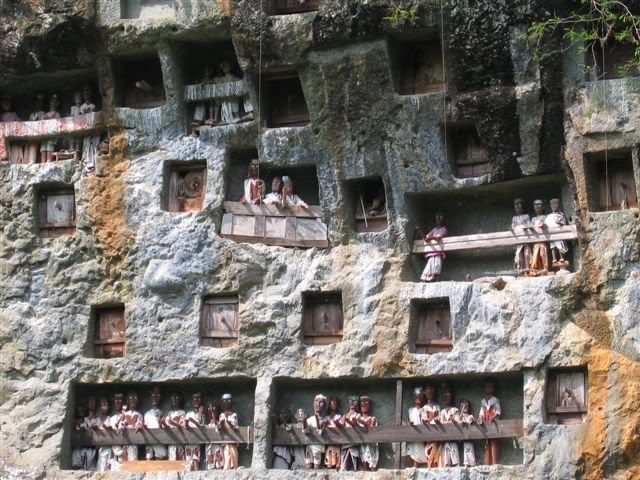

We noticed that despite Death being at the centre of the Torajan life and economy, the atmosphere was in no way macabre. In a noble household, the deceased can remain in the house for years, in a special casket in a designated room, until the family fulfils the requirements for a funeral ceremony. It is quite a lengthy and complicated process that we will try to explain roughly... A certain amount of buffalos must be gathered for sacrifice. At least 24 for a noble, 12 for a rich man and 1 for a serf. An effigy of the dead (a "tau-tau"), must be carved by a bomoh. This also requires a sacrifice. The buffalos will accompany a part of the deceased's soul on his trip back to the sky, the earthly portion of the soul staying in the tau-tau, which will be placed in front of the grave. Cockfights are organised to raise money. Below, a row of tau-taus guarding graves:

On our second stop in Ponding, we stayed at Deny's grandmother’s. Past this, we entered Tator district. The transition was smooth. In those remote valleys, Mamasa and Tator architecture cohabit. An up curved Tator roof:

On our arrival in Bittuang, we got the news that the funeral had been postponed... Instead of waiting there for 3 days, we decided to continue down to Rantepao by bus, and come back later.

Rantepao is the traditional centre of Tanah Toraja. It lies on a flat and wide plateau surrounded by steep mountains. The region is relatively wealthy and has much more infrastructure than what we had seen in the mountains. Tourism is relatively well developed there, and we felt it in the attitude of the locals... We would usually get greeted with a cry for "gula!", meaning "sweets!", to which we responded "habis!"/"no more!". On some rare occasions, some pushed as far as "wang!"/"money!". Even if, like everywhere in Indonesia, the number of visitors have declined drastically since the first Bali bombing in 2002, the bad habits stick and young mothers were candidly teaching their babies to beg for sweets.

The region around Rantepao has a great variety of graves. Ranging from impressive galleries of tau-taus, here at the royal graves of Lemo...

...to baby graves in trees, funeral caves and chambers carved in rock faces and big boulders making them look like apartment houses. In the Torajan tradition, the body must not be buried underground because it is believed the soul can’t live there. Only serfs get buried underground, following the Christian or Muslim tradition, because it is much cheaper to do so.

We were lucky to stumble on the morning livestock market taking place every 6 days in Bola, where buffalos and pigs are traded, mainly destined for funeral. We were particularly impressed by the rows of live pigs, tied up awaiting their buyers.

A buffalo and his owner:

After a few days in the lowlands, we were back in Bittuang for the funeral, which they call "pesta orang mati" ("dead man's party"). The ceremony we attended was for two noble people, a grandmother and her nephew who died in the same year. Quite an unconventional event...

On the first day, the coffin is brought to the tower at the of the centre temporary funeral village. Cock and bullfights traditionally take place. But in this case, the woman priest of the Christian church was of the deceased's family, and she expressly forbid the fights!

We skipped the first day and arrived on the second day of the funeral, when the extended family of the deceased greets their guests. On our arrival, we were surprised to see that Deny and his clan were waiting for us. We were to be their guests for the next days. Together, we proceeded to the entrance of the village, where we waited to be called in. Then the whole clan formed a column to enter the funeral village carrying pigs and other gifts. We brought a carton of the popular "Gudang Garam Surya" kreteks (clove cigarettes) and a kilo of white sugar.

After crossing the entrance gate, we passed the quarters where the host family lived for the length of the ceremonies, turned around the coffin-tower, and came back past the quarters of the guests to enter a big covered bamboo platform near the entrance. There, men and women were directed to different compartments and were officially received by the family. There was a bit of polite conversation, and the men were offered kreteks. A circle of Ma'Badong singers formed and welcomed the guests with a haunting chant.

After this, we allocated to our quarters on the southern side of the village where we were served drinks and biscuits. From there, we could observe the same procedure being repeated for each visiting clan.

Behind the houses, pigs squealed as they were being slaughtered. The carcasses were first roasted, then cut into pieces to be cooked over the fire in bamboos tubes in a fashion quite similar to the Ibans' in Sarawak.

After all the guests had been received, meat from a sacrificed albino buffalo was distributed to the visitors. Representatives of the clans were called under a raised platform to pick up their share, quite unceremoniously thrown down to them!

In the late afternoon, the rain suddenly interrupted the chitchatting, and all the guests left. Later, we heard from Deny that this wouldn't have happened if they had hired a bomoh to perform incantations to keep the rain away. But good bomohs are expensive… This was a hint that the joint funeral was maybe organised to cut down costs. Indeed, there were only 24 buffalos waiting to be sacrificed, instead of the minimum of 48 that separate ceremonies would have required for people of such rank...

The 3rd day of this funeral was identical to the 2nd. An extra day was needed to greet the many guests. So instead of idling there, we accepted Deny's family’s invitation to follow them back to Ponding to see cock fights. These were for the reburial ceremony of important ancestors. Ton such occasions, the bones are taken out to be dusted and placed in the sun before being wrapped in new clothes and put back in their graves. Before the reburial, the graves have to be revamped and a few sacrifices have to be performed. The family of the dead organised 12 days of cock fighting and gambling to raise some funds, collecting a percentage on the bets. As those activities are illegal in Indonesia, the “bush casino” was hidden away in the hills. They were temporary stalls selling food, drinks and cigarettes around the fighting arena. Men came from quite far to participate in the event, and sometimes slept there.

Fighting cocks are trained, pampered and massaged for months in preparation for the fight. At the venue, the owners of the birds minutely assess their potential opponents, ensuring the fight is balanced. When both owners agree on the match and the sum they will bet on their protégés, they announce themselves at the judge's desk and wait to be called in the arena. The cocks are dressed with a sharp knife on their left foot by a designated specialist.

Around the arena, the spectators raise their own bets. The fight itself is very short. As soon as a fighter is wounded, it is carried away by the referees and placed over a pole. The winner is brought over to pick him once on the head and a leg of the suffering loser is swiftly chopped off for the owner of the winner. The maimed bird is then let to die in a corner...

We went back to Bittuang for the 4th day of the funeral, when the remainder of the buffalos are slaughtered and the coffins brought to the grave. The place was strangely half empty and the atmosphere slightly tense. We were kindly invited by the hosts to drink coffee in their living quarters. From there, we had a good view of the scene. The buffalos were brought in and tied to poles to await their fate. A buffalo was auctioned off for the Church. Then a mini-riot flared up. Some hotheaded members of the host family picked up a fight and had to be separated.

We found out there was a disagreement within the family on where the bodies were to be buried and where the sacrifices were to take place. The Bittuang branch wanted everything in their village, whereas the Ponding relatives wanted to bring back one coffin to their village and sacrifice half of the buffalos there... This issue had been lingering for a while, but nobody seemed to have enough authority to settle the matter. The fighting didn’t help everyone was confused on what to do next. Someone went to fetch the policeman. We waited. Nobody came back. Then it started to rain, and everybody went home, leaving the buffalos peacefully grazing around their pole!

We don't know how the story eventually ended. We didn't have time to wait any longer. We'd had already spent 12 days in Torajaland, much more than we planned, and we felt it was time for us to move on!

Diving On The Moon

To put it plainly, diving in Lembeh is amazing! The narrow straits separating the small island of Lembeh from the northern tip of Sulawesi contains some of the most unusual marine fauna. They are some small coral walls, but most divers come here to scan the black sandy slopes and coral rubble. That’s where the uncanniest discoveries are made!

On each of our 18 dives there, we saw at least something new. Compared to Mabul, Malaysia’s “macro Mecca” beside Sipadan (see Sabah report), we found the visibility in Lembeh much better, and the variety of species much greater. The current was similar, that is not too strong.

Well camouflaged members of the scorpionfish family were lurking everywhere: cockatoo waspfish, paper fish, velvet fish, ambon scorpionfish, rock fish, spiny devilfish, dwarf lionfish, etc. Also well hidden were quite a number of different frogfishes (painted-, clown-, striated-, giant- and the fearsome hairy frogfish) and other amusing fish (cowfish, weedy filefish, ball-like juvenile puffers, flying gurnards, etc.).

All branches of the seahorse family tree were represented: some big seahorses (yellow, brown or white), the unusual ground-dwelling seamoth with its wings, pseudo-legs and little trump, many pipefish (slender-, yellow-ringed-, robust-, and the leaf like ornate ghost pipefish) and the rare pygmy seahorse. Incontestably the star of the straits, just a few millimetres long blending perfectly in the soft fan corals, this cute seahorse can only be uncovered by expert eyes!

Lembeh is also a paradise for nudibranch-, sea slug-, and flatworm-lovers. We saw most of those pictured in the "South-East Asia Reef Guide" (a reference), and more…

The gastropod fauna was exceptionally rich: mimic octopus (who change colours and imitate the shape and behaviour of other marine animals like flounders and sea snakes to escape predators), wonderpus (an elusive fellow who like to bury in the sand with just his periscopic eyes emerging to survey the neighbourhood - exposed in the picture below!), reef octopus, flamboyant cuttlefish and other sepias.

The large variety of shrimps (including many bright green mantis), small crabs, tiny squat lobsters, strange sea urchins, etc, kept us busy going through the dive centre’s reference books to fill up the pages of our log books.

Last but not least, we should mention Sulawesi Dive Quest, the friendly and enthusiastic dive operator with whom we stayed on Lembeh. The dive masters, all locals, were exceptional at spotting critters that our untrained eyes would not have seen. Dive time was always above 1 hour, which is unusually generous in the business. And they let us negotiate a very good deal with them... So highly recommended!

Thanks to Nan from SDQ, and our fellow divers Sandy and Kat from Singapore for the underwater photos.

Beyond The Wallace Line

Alfred Russel Wallace, the famous 19th century naturalist, identified a line of separation between the Oriental and Australasian fauna. He drew his line running between the islands of Bali and Lombok, and continuing between Borneo and Sulawesi. The next paragraph is quoted from "The Malay Archipelago", his authoritative work published in 1869, and written after spending 8 years exploring what is today Malaysia and Indonesia.

"[] we shall find that all islands from Celebes and Lombock eastwards exhibit almost as close a resemblance to Australia and New Guinea as the Western islands do to Asia. It is well known that the natural productions of Australia differ from those of Asia more than those of the four ancient quarters of the world differ from each other. [] If we travel from [] Borneo to Celebes [], the difference is [] striking. In the first, the forests abound in monkeys of many kinds, wild cats, deer, civets, and otters, and numerous varieties of squirrels []. In the latter, none of these occur; but the prehensile-tailed Cuscus is almost the only terrestrial mammal seen, except wild pigs, which are found in all the islands, and deer (which have probably been recently introduced) in Celebes and the Moluccas. The birds which are most abundant in the Western Islands are woodpeckers, barbets, trogons, fruit-thrushes, and leaf thrushes: they are seen daily, and form the great ornithological features of the country. In the Eastern Islands these are absolutely unknown, honeysuckers and small lories being the most common birds; so that the naturalist feels himself in a new world, and can hardly realise that he has passed from the one region to the other in a few days, without ever being out of sight of land..."

To verify this, we went to Tangkoko National Park, whose peaks are visible just across the Lembeh straits.

Tangkoko park lies in the Minahasan highlands, who make up for the most part of northern tip of Sulawesi. A very Christian area, where each village has at least 5 churches competing for the souls of the inhabitants. Methodists, Protestants, Catholics, Pantecostist, True Jesus Church, etc all trying to build smarter and bigger temples...

Minahasan Sundays are very festive. People of all ages enjoy their afternoon in balls with deafening soundsystems. We came across a number of venerable mamas in hats and church attire being dragged home in a state of advanced inebriety!

In the early morning of our first day of exploration, 3 small hornbills flew over us just as we crossed the gates of the park,. Then we saw a big wild cat, which, according to Wallace, was not supposed to be there. There were also at least 2 species of kingfishers, pigeons, minahbirds... So far, nothing too different from Borneo...

In the evening, we hired a park ranger to show us the tarsiers, tiny nocturnal primates who sleeps in hollow trees during the day (see picture below). On this trek, we caught good views of hornbills; they had large yellow beaks and a magnificent red horn. On our way back, it was pitch dark and we found tarantulas on some trees. They were slightly larger than those we saw on Borneo.

The next morning, we went with the same ranger in search of the black macaques, which are endemic to Sulawesi. They have very short tails, and are black instead of grey or beige. We eventually found 2 groups, not far from each other.. They had apparently had a territorial scuffle and a baby in one group was wounded. According to Wallace, there shouldn’t be monkeys on Sulawesi… We also found traces of a cuscus, but we unfortunately didn't see this shy relative of the koala. But we finally saw some flying lizards in action! Our guide managed to catch one, who demonstrated his gliding skills, unfolding his “wings”, which are in fact extensions of his ribs, to escape.

So our observations did not confirm the Wallace line, which still appear in tourist brochures. This wasn't a surprise; we are not the first to invalidate this proposition! A straightforward idea in itself, Wallace's line became the subject of a complicated set of revisions, clarified in the 1920s by the creation of Wallacea, a region which sidesteps definite boundaries by encapsulating Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara and Maluku as a biological transition zone between Asia and Australasia.

After 3 days in Tangkoko, we dragged ourselves back to Manado, the main city of Northern Sulawesi, from where we flew back to Singapore a couple of days later. We didn't have the energy to go around much, but it looked quite neat and wealthy for an Indonesian city, even if there was nothing spectacular about it. The population was eclectic: Minahasans, Chinese, Javanese, some Western tourists (mostly divers)... Somehow, it remained us of Kota Kinabalu in Sabah.

Sulawesi is a large island that extends its peninsulas like tentacles East of Borneo. Its convolutions led the Portuguese to believe, on first coming here, that they found a group of islands, which they named "the" Celebes, not realising the peninsulas were connected.

Sulawesi's geography is very rugged. Separated by steep mountains ranges, the people of the different peninsulas, developed distinct cultures. On this trip, we focused on the Southwestern finger, which contains most of the lowlands and population of Sulawesi, and the Northern tip, which has some exceptional dive sites and good national parks. We took a flight (1h30) between those regions, avoiding the troubled Poso region in central Sulawesi and a harassing 5 days bus trip.

We hit Sulawesi end of October, at the beginning of the rainy season. In the morning, it was usually sunny. Being near the equator, the light turned very bright after 10am, and it felt hot and heavy. In the early afternoon, clouds would appear and we had rain almost every evening. Usually short showers, seldom downpours that continued during the night. The quality of the photos suffered a bit from the poor light conditions. This was aggravated by the fact that our digital camera, now in its 16th month of travelling, showed signs of exhaustion and had some problems in focusing and evaluating the brightness. A bit like us!

On Bugis And Makassarese

We started our ramblings in Makassar, the biggest city of Sulawesi and a busy commercial hub.

The population of the Southwestern peninsula is in majority Bugis and Makassarese. Theodora Benson, who travelled to Sulawesi in the 1930s wrote: "The Bugis and the Makassarese of the South are always spoken as two distinct races, but in descriptions of them no distinction between them appears at all except that their languages (of the Malayo-Javanese group) are very slightly different, at that the Bugis are a bit more seagoing and the Makassarese more agricultural. They are Mohammedans, with a touch of Hinduism and paganism, and women have a high and favourable position. They build magnificent prahus and navigate fearlessly. [] On many distant islands, a Bugis colony is found. They are energetic and spirited people, devoted to fun and gambling and good trade".

The distinction between Makassarese and Bugis probably came from the fact they were never really unified, and had historically had many competing kingdoms. The Dutch made use of those divisions to eventually completely subjugate them in 1909. We should also add that the Europeans, whose ships they often hijacked, feared them a lot. This earned the Bugis a lasting reputation as bloodthirsty pirates!

Makassar still has some remnants of the past, like Fort Rotterdam, a fortress whose origin is contested. The name would suggest the Dutch built it, but many think a Makassarese fort stood there before. There is also the more interesting and lively Paotere port. Paotere is the bustling base of what is probably the last non-motorised commercial fleet in the world. The majestic prahus, powered solely by the wind blowing in their sails, sternly await the cargo they'll be delivering all across the Indonesian archipelago.

According to our guidebook, a visit to Makassar is not complete without a meal at the cheap nocturnal seafood stalls along the sea promenade, which are so highly recommended as to be one of the highlights of Sulawesi! In fact, small affairs with dubious hygiene selling low-grade quality that failed to impress us. Else, we experienced the usual heat, stench and chaotic traffic of thousands of minibuses and tri-cycles honking and ringing every time they past us. But most of the people were very nice. For example, the tourist information our guidebook indicated, in fact a police station in the dusty and pointless museum, had only their total lack of knowledge on the city to match their eagerness to help and curiosity! Leaving their office, we were not quite sure they had seen any tourists before us...

Leaving Makassar was like breathing again. We enjoyed rather agreeable bus rides through coastal lowlands covered by wet rice fields, which offer a breathtaking tableau from the airplane, passing peaceful small towns and villages. We didn't explore much of the Bugis countryside though.

On our way to the Toraja highlands, we stayed one night in Polewali on the west coast of the peninsula, in an extremely friendly home-stay who hadn't seen many foreign guests before. The next morning was a Sunday. We took a walk to the weekly market, passing a few interesting ships on the beach. The weather was clouded and rainy, so we decided not to go to the Mandar heartland a couple of hours further along the coast. We proceeded instead directly to the Western Torajan highlands.

On our way back from the highlands, we did a stop in Sengkang, on the East coast of the peninsula. . Sengkang is on the shores of a lake system, on which fishermen communities live in floating shacks. A silk industry has been implemented in this region since the beginning of the 1990s, with the help of Thailand. We hoped to find some good material for Claudia's mother, but the quality, patterns and colours on offer in town were disappointing.

Life And Death In Torajaland

What we call Torajaland spans over two districts: Western Toraja (better known as Mamasa by the locals), and Tanah Toraja (also very “Indonesianly” abbreviated Tator). They are slight differences between the people of the two areas, most notably in the architecture (the Tator roofs are more up curved), the dialects and the art (they use different symbols, but the base colours stay the same). Typical carvings on the front of a house:

The word Toraja comes from the Bugis, and means "mountain people". There was never a unified Toraja kingdom. The villages had all their own nobility and used to fight quite often. Human sacrifices at funeral ceremonies and headhunting were also practised.

We started our Toraja circuit in Mamasa, which is the capital of the western district. The 90km trip from Polewali took 5 hours up a winding road in a new Kijang 4-wheel-drive. Mamasa itself had a few nice traditional houses and lots of half empty government buildings.

The bucolic walks to the surrounding villages were more attractive. There, we were once again the centre of attention; children springing out of nowhere like jack-in-the-box quipping "hello mister!", and adults continuously inquiring about where we wanted to go ("mau ke mana?" a common Indonesian greeting).

We spent a few days in Mamasa to gather some information on the region, the guidebooks just sparing at most a few lines on the subject. We met some helpful locals at the guesthouse, and we managed to gather intelligence from them around a few rounds of "balok" (a homemade mild palm wine). They told us about an important funeral in Bittuang, which happened to be on our itinerary. They also presented us to the Governor of the Mamasa province, who, after self-importantly telling us about tourism promotion in his district, wrote us a letter of recommendation.

So, we started our trek across Torajaland with this official blessing. The walk was going to take 3 days. Shortly after we started, we met Deny, a local nobleman living in an impressive traditional house. He invited us in for tea. He had studied anthropology, his English was very good and he was a trove of information on Western Toraja. He also had planned to go to the big funeral in Bittuang. When he finally proposed to guide us for a small fee, we accepted.

The path was not hard to find, we just had to follow the incredibly bumpy "Trans-Mamasa highway", not really suited for motorised vehicles. Deny showed us a few shortcuts and cooler alternatives, but most of the time we had to use the unshaded, stony road at the mercy of the sun.

En route, we learned about the strict Toraja class system (4 levels, from nobility down to serfdom), some symbols on houses and rice barns, the importance of cardinal directions in their cosmology, the differences between Mamasa and Tator, funeral ceremonies, reburial rituals, weddings, etc. We often stopped to chat under the ornate rice barns with Deny’s friends and relatives, and thus got acquainted with Torajan everyday life.

We saw that despite being officially in majority Christians, the Torajans still follow many rites and traditions of their ancient animist faith. Indonesian syncretism again! In Timbaan, the small hamlet where we did our first stop, the old bomoh (i.e. shaman) came with his flute to play traditional music.

We noticed that despite Death being at the centre of the Torajan life and economy, the atmosphere was in no way macabre. In a noble household, the deceased can remain in the house for years, in a special casket in a designated room, until the family fulfils the requirements for a funeral ceremony. It is quite a lengthy and complicated process that we will try to explain roughly... A certain amount of buffalos must be gathered for sacrifice. At least 24 for a noble, 12 for a rich man and 1 for a serf. An effigy of the dead (a "tau-tau"), must be carved by a bomoh. This also requires a sacrifice. The buffalos will accompany a part of the deceased's soul on his trip back to the sky, the earthly portion of the soul staying in the tau-tau, which will be placed in front of the grave. Cockfights are organised to raise money. Below, a row of tau-taus guarding graves:

On our second stop in Ponding, we stayed at Deny's grandmother’s. Past this, we entered Tator district. The transition was smooth. In those remote valleys, Mamasa and Tator architecture cohabit. An up curved Tator roof:

On our arrival in Bittuang, we got the news that the funeral had been postponed... Instead of waiting there for 3 days, we decided to continue down to Rantepao by bus, and come back later.

Rantepao is the traditional centre of Tanah Toraja. It lies on a flat and wide plateau surrounded by steep mountains. The region is relatively wealthy and has much more infrastructure than what we had seen in the mountains. Tourism is relatively well developed there, and we felt it in the attitude of the locals... We would usually get greeted with a cry for "gula!", meaning "sweets!", to which we responded "habis!"/"no more!". On some rare occasions, some pushed as far as "wang!"/"money!". Even if, like everywhere in Indonesia, the number of visitors have declined drastically since the first Bali bombing in 2002, the bad habits stick and young mothers were candidly teaching their babies to beg for sweets.

The region around Rantepao has a great variety of graves. Ranging from impressive galleries of tau-taus, here at the royal graves of Lemo...

...to baby graves in trees, funeral caves and chambers carved in rock faces and big boulders making them look like apartment houses. In the Torajan tradition, the body must not be buried underground because it is believed the soul can’t live there. Only serfs get buried underground, following the Christian or Muslim tradition, because it is much cheaper to do so.

We were lucky to stumble on the morning livestock market taking place every 6 days in Bola, where buffalos and pigs are traded, mainly destined for funeral. We were particularly impressed by the rows of live pigs, tied up awaiting their buyers.

A buffalo and his owner:

After a few days in the lowlands, we were back in Bittuang for the funeral, which they call "pesta orang mati" ("dead man's party"). The ceremony we attended was for two noble people, a grandmother and her nephew who died in the same year. Quite an unconventional event...

On the first day, the coffin is brought to the tower at the of the centre temporary funeral village. Cock and bullfights traditionally take place. But in this case, the woman priest of the Christian church was of the deceased's family, and she expressly forbid the fights!

We skipped the first day and arrived on the second day of the funeral, when the extended family of the deceased greets their guests. On our arrival, we were surprised to see that Deny and his clan were waiting for us. We were to be their guests for the next days. Together, we proceeded to the entrance of the village, where we waited to be called in. Then the whole clan formed a column to enter the funeral village carrying pigs and other gifts. We brought a carton of the popular "Gudang Garam Surya" kreteks (clove cigarettes) and a kilo of white sugar.

After crossing the entrance gate, we passed the quarters where the host family lived for the length of the ceremonies, turned around the coffin-tower, and came back past the quarters of the guests to enter a big covered bamboo platform near the entrance. There, men and women were directed to different compartments and were officially received by the family. There was a bit of polite conversation, and the men were offered kreteks. A circle of Ma'Badong singers formed and welcomed the guests with a haunting chant.

After this, we allocated to our quarters on the southern side of the village where we were served drinks and biscuits. From there, we could observe the same procedure being repeated for each visiting clan.

Behind the houses, pigs squealed as they were being slaughtered. The carcasses were first roasted, then cut into pieces to be cooked over the fire in bamboos tubes in a fashion quite similar to the Ibans' in Sarawak.

After all the guests had been received, meat from a sacrificed albino buffalo was distributed to the visitors. Representatives of the clans were called under a raised platform to pick up their share, quite unceremoniously thrown down to them!

In the late afternoon, the rain suddenly interrupted the chitchatting, and all the guests left. Later, we heard from Deny that this wouldn't have happened if they had hired a bomoh to perform incantations to keep the rain away. But good bomohs are expensive… This was a hint that the joint funeral was maybe organised to cut down costs. Indeed, there were only 24 buffalos waiting to be sacrificed, instead of the minimum of 48 that separate ceremonies would have required for people of such rank...

The 3rd day of this funeral was identical to the 2nd. An extra day was needed to greet the many guests. So instead of idling there, we accepted Deny's family’s invitation to follow them back to Ponding to see cock fights. These were for the reburial ceremony of important ancestors. Ton such occasions, the bones are taken out to be dusted and placed in the sun before being wrapped in new clothes and put back in their graves. Before the reburial, the graves have to be revamped and a few sacrifices have to be performed. The family of the dead organised 12 days of cock fighting and gambling to raise some funds, collecting a percentage on the bets. As those activities are illegal in Indonesia, the “bush casino” was hidden away in the hills. They were temporary stalls selling food, drinks and cigarettes around the fighting arena. Men came from quite far to participate in the event, and sometimes slept there.

Fighting cocks are trained, pampered and massaged for months in preparation for the fight. At the venue, the owners of the birds minutely assess their potential opponents, ensuring the fight is balanced. When both owners agree on the match and the sum they will bet on their protégés, they announce themselves at the judge's desk and wait to be called in the arena. The cocks are dressed with a sharp knife on their left foot by a designated specialist.

Around the arena, the spectators raise their own bets. The fight itself is very short. As soon as a fighter is wounded, it is carried away by the referees and placed over a pole. The winner is brought over to pick him once on the head and a leg of the suffering loser is swiftly chopped off for the owner of the winner. The maimed bird is then let to die in a corner...

We went back to Bittuang for the 4th day of the funeral, when the remainder of the buffalos are slaughtered and the coffins brought to the grave. The place was strangely half empty and the atmosphere slightly tense. We were kindly invited by the hosts to drink coffee in their living quarters. From there, we had a good view of the scene. The buffalos were brought in and tied to poles to await their fate. A buffalo was auctioned off for the Church. Then a mini-riot flared up. Some hotheaded members of the host family picked up a fight and had to be separated.

We found out there was a disagreement within the family on where the bodies were to be buried and where the sacrifices were to take place. The Bittuang branch wanted everything in their village, whereas the Ponding relatives wanted to bring back one coffin to their village and sacrifice half of the buffalos there... This issue had been lingering for a while, but nobody seemed to have enough authority to settle the matter. The fighting didn’t help everyone was confused on what to do next. Someone went to fetch the policeman. We waited. Nobody came back. Then it started to rain, and everybody went home, leaving the buffalos peacefully grazing around their pole!

We don't know how the story eventually ended. We didn't have time to wait any longer. We'd had already spent 12 days in Torajaland, much more than we planned, and we felt it was time for us to move on!

Diving On The Moon

To put it plainly, diving in Lembeh is amazing! The narrow straits separating the small island of Lembeh from the northern tip of Sulawesi contains some of the most unusual marine fauna. They are some small coral walls, but most divers come here to scan the black sandy slopes and coral rubble. That’s where the uncanniest discoveries are made!

On each of our 18 dives there, we saw at least something new. Compared to Mabul, Malaysia’s “macro Mecca” beside Sipadan (see Sabah report), we found the visibility in Lembeh much better, and the variety of species much greater. The current was similar, that is not too strong.

Well camouflaged members of the scorpionfish family were lurking everywhere: cockatoo waspfish, paper fish, velvet fish, ambon scorpionfish, rock fish, spiny devilfish, dwarf lionfish, etc. Also well hidden were quite a number of different frogfishes (painted-, clown-, striated-, giant- and the fearsome hairy frogfish) and other amusing fish (cowfish, weedy filefish, ball-like juvenile puffers, flying gurnards, etc.).

All branches of the seahorse family tree were represented: some big seahorses (yellow, brown or white), the unusual ground-dwelling seamoth with its wings, pseudo-legs and little trump, many pipefish (slender-, yellow-ringed-, robust-, and the leaf like ornate ghost pipefish) and the rare pygmy seahorse. Incontestably the star of the straits, just a few millimetres long blending perfectly in the soft fan corals, this cute seahorse can only be uncovered by expert eyes!

Lembeh is also a paradise for nudibranch-, sea slug-, and flatworm-lovers. We saw most of those pictured in the "South-East Asia Reef Guide" (a reference), and more…

The gastropod fauna was exceptionally rich: mimic octopus (who change colours and imitate the shape and behaviour of other marine animals like flounders and sea snakes to escape predators), wonderpus (an elusive fellow who like to bury in the sand with just his periscopic eyes emerging to survey the neighbourhood - exposed in the picture below!), reef octopus, flamboyant cuttlefish and other sepias.

The large variety of shrimps (including many bright green mantis), small crabs, tiny squat lobsters, strange sea urchins, etc, kept us busy going through the dive centre’s reference books to fill up the pages of our log books.

Last but not least, we should mention Sulawesi Dive Quest, the friendly and enthusiastic dive operator with whom we stayed on Lembeh. The dive masters, all locals, were exceptional at spotting critters that our untrained eyes would not have seen. Dive time was always above 1 hour, which is unusually generous in the business. And they let us negotiate a very good deal with them... So highly recommended!

Thanks to Nan from SDQ, and our fellow divers Sandy and Kat from Singapore for the underwater photos.

Beyond The Wallace Line

Alfred Russel Wallace, the famous 19th century naturalist, identified a line of separation between the Oriental and Australasian fauna. He drew his line running between the islands of Bali and Lombok, and continuing between Borneo and Sulawesi. The next paragraph is quoted from "The Malay Archipelago", his authoritative work published in 1869, and written after spending 8 years exploring what is today Malaysia and Indonesia.

"[] we shall find that all islands from Celebes and Lombock eastwards exhibit almost as close a resemblance to Australia and New Guinea as the Western islands do to Asia. It is well known that the natural productions of Australia differ from those of Asia more than those of the four ancient quarters of the world differ from each other. [] If we travel from [] Borneo to Celebes [], the difference is [] striking. In the first, the forests abound in monkeys of many kinds, wild cats, deer, civets, and otters, and numerous varieties of squirrels []. In the latter, none of these occur; but the prehensile-tailed Cuscus is almost the only terrestrial mammal seen, except wild pigs, which are found in all the islands, and deer (which have probably been recently introduced) in Celebes and the Moluccas. The birds which are most abundant in the Western Islands are woodpeckers, barbets, trogons, fruit-thrushes, and leaf thrushes: they are seen daily, and form the great ornithological features of the country. In the Eastern Islands these are absolutely unknown, honeysuckers and small lories being the most common birds; so that the naturalist feels himself in a new world, and can hardly realise that he has passed from the one region to the other in a few days, without ever being out of sight of land..."

To verify this, we went to Tangkoko National Park, whose peaks are visible just across the Lembeh straits.

Tangkoko park lies in the Minahasan highlands, who make up for the most part of northern tip of Sulawesi. A very Christian area, where each village has at least 5 churches competing for the souls of the inhabitants. Methodists, Protestants, Catholics, Pantecostist, True Jesus Church, etc all trying to build smarter and bigger temples...

Minahasan Sundays are very festive. People of all ages enjoy their afternoon in balls with deafening soundsystems. We came across a number of venerable mamas in hats and church attire being dragged home in a state of advanced inebriety!

In the early morning of our first day of exploration, 3 small hornbills flew over us just as we crossed the gates of the park,. Then we saw a big wild cat, which, according to Wallace, was not supposed to be there. There were also at least 2 species of kingfishers, pigeons, minahbirds... So far, nothing too different from Borneo...

In the evening, we hired a park ranger to show us the tarsiers, tiny nocturnal primates who sleeps in hollow trees during the day (see picture below). On this trek, we caught good views of hornbills; they had large yellow beaks and a magnificent red horn. On our way back, it was pitch dark and we found tarantulas on some trees. They were slightly larger than those we saw on Borneo.

The next morning, we went with the same ranger in search of the black macaques, which are endemic to Sulawesi. They have very short tails, and are black instead of grey or beige. We eventually found 2 groups, not far from each other.. They had apparently had a territorial scuffle and a baby in one group was wounded. According to Wallace, there shouldn’t be monkeys on Sulawesi… We also found traces of a cuscus, but we unfortunately didn't see this shy relative of the koala. But we finally saw some flying lizards in action! Our guide managed to catch one, who demonstrated his gliding skills, unfolding his “wings”, which are in fact extensions of his ribs, to escape.

So our observations did not confirm the Wallace line, which still appear in tourist brochures. This wasn't a surprise; we are not the first to invalidate this proposition! A straightforward idea in itself, Wallace's line became the subject of a complicated set of revisions, clarified in the 1920s by the creation of Wallacea, a region which sidesteps definite boundaries by encapsulating Sulawesi, Nusa Tenggara and Maluku as a biological transition zone between Asia and Australasia.

After 3 days in Tangkoko, we dragged ourselves back to Manado, the main city of Northern Sulawesi, from where we flew back to Singapore a couple of days later. We didn't have the energy to go around much, but it looked quite neat and wealthy for an Indonesian city, even if there was nothing spectacular about it. The population was eclectic: Minahasans, Chinese, Javanese, some Western tourists (mostly divers)... Somehow, it remained us of Kota Kinabalu in Sabah.